Originally published by Outside Collective

Words by James Huang

Ritte doesn’t peg its latest Esprit model as an aero road racer, or an ultralight climbing bike, or an all-road machine. Instead, the company says it’s, “designed to excel on your road ride – whatever it may be.” Sounds weirdly vague, no?

But as it turns out, that amorphous nature is rather apt. It’s not at all aero, it’s light-but-not-crazy-light, it’s snappy and responsive, it handles really well, it has room for big tires, it looks good, and perhaps most importantly, it just feels fantastic when you’re riding it. In not trying to be any one thing in particular, it ends up being pretty dang good at a lot of things.

The short of it: Ritte’s fourth-generation carbon road racer, updated with a lighter frame, fully hidden cable routing, and a sleeker shape.

Good stuff: Wonderfully lively ride feel, competitively light, sharp looks, a good range of customization options, surprisingly impressive house-brand wheels.

Bad stuff: So-so value, questions about the manufacturing quality, arguably too-quick handling.

Frites and mayo for everyone

Ritte was founded more than a dozen years ago with more than a little bit of camp. Since its inception, the brand has leaned heavily on the mystique of Belgian road racing culture. In fact, “ritte” supposedly means “to ride” in Flemish (although a native Flemish speaking EC member says otherwise). Regardless, the brand has always been based in California and – at least initially – the frames were open-mold models made in Asia. The bikes are emblazoned with the red, blue, and yellow colors of the Belgian national team, the head tube logo incorporates the lion of Flanders, and there are more than a few references to all things Belgian in the company’s marketing materials and web site, but aside from that, there’s never been a concrete connection to Belgium that I’m aware of.

It wasn’t intended to be deceptive, but rather a more tongue-in-cheek stab at typical bike industry norms with a bit of self-deprecating humor for added flavor.

Still, Ritte was a brand essentially built on marketing – but what brilliant marketing it was.

Ritte has matured a lot since then, and the bikes have, too. The company now offers road, all-road, and gravel bikes in three different materials, including a US-made custom titanium model using a 3D-printed front end. The open-mold days have faded in the rearview mirror, replaced by a range that now feels like it has actual substance instead of just airy hype. Even the frame geometry is penned by legendary custom builder Tom Kellogg.

Ritte’s latest carbon fiber model is the Esprit, a road bike that – strangely enough in this day and age of hyper-specialization – doesn’t seem to aspire to excel at anything in particular.

The frame design itself comes across as fairly unremarkable. The down tube is distinctly oversized with a sort of rounded-octagonal cross-section, the similarly overstuffed chainstays sport a rectangular shape, and the seat tube starts out round up top, but becomes more rectangular and flared as it meets the bottom bracket shell. All of that is presumably in place to boost frame stiffness under power.

The top tube also features a rounded rectangular cross-section (but oriented horizontally as compared to the chainstays’ more vertical layout), while both the asymmetrical tapered seat tube and straight, small-diameter seatstays are predominantly round. Up top is a totally normal 27.2 mm-diameter round seatpost, held in place by a nicely integrated wedge-type binder tucked into the top tube. While the lower half of the frame seems to prioritize rigidity, the top half seems to put a much bigger emphasis on ride quality.

Up front, the crown of the matching fork blends nicely into the surrounding head tube and down tube area, and just as apparently everyone expects for a modern higher-end road bike these days, there’s a one-piece carbon fiber bar-and-stem combo with control lines that are completely hidden from view. Ritte goes the fully internal route here, running the brake hoses through the inside of the bar and stem before taking a downward turn alongside the steerer tube and through the upper headset bearing before snaking their way through the rest of the frame and fork. The system is designed solely for use with electronic drivetrains (wired or wireless); Shimano Di2 batteries are housed inside the seatpost.

Some other notable details include clearance for 700c tires up to 35 mm-wide (measured width), a removable aluminum front derailleur mount for a cleaner look should you prefer to run a 1x drivetrain, a SRAM Universal Derailleur Hanger, a narrow-format T47 threaded bottom bracket shell, and a dedicated direct-mount front brake interface for 160 mm-diameter rotors only with bolts that feed in from the front and are concealed by a little plastic cover.

Claimed weight for a medium Esprit frame is “sub-800 g” in the raw black finish. The “Rossa Corsa Red” (surely this should be in Flemish, not Italian, no?) reportedly adds about another 25 g.

Models, colors, sizes, and pricing

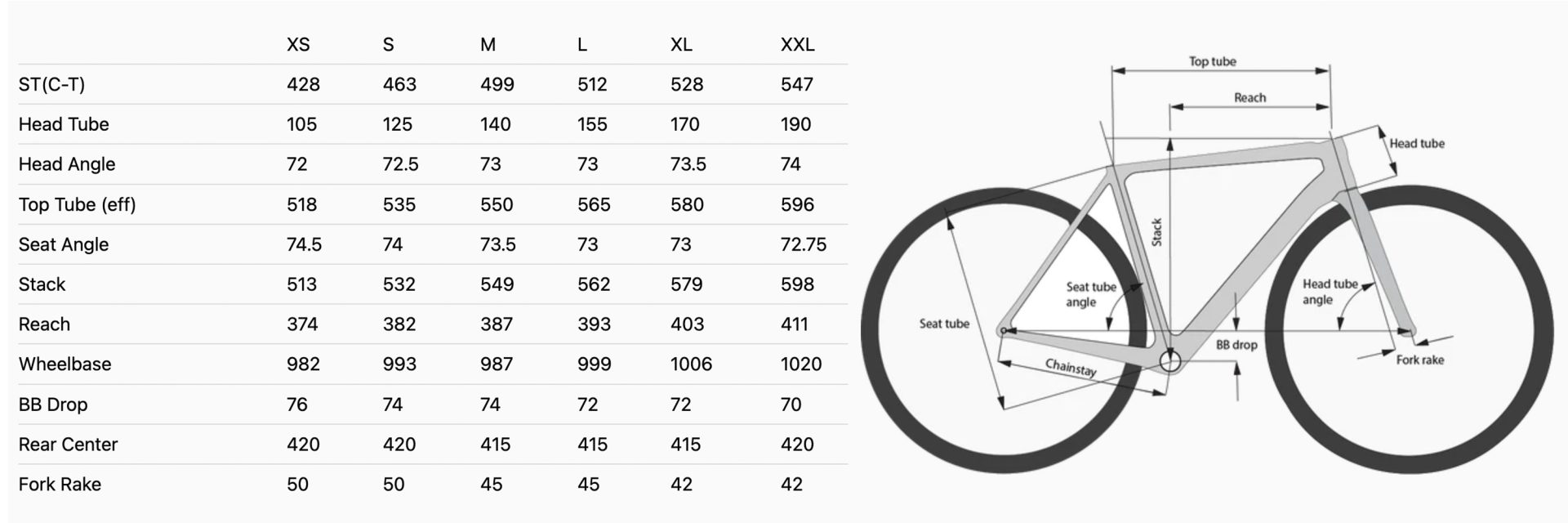

Ritte offers the Esprit in four complete builds or as a bare frameset, all of which are available with either a raw black or painted red finish and (impressively for such a small brand) a choice of six sizes with reach dimensions ranging from just 374 mm all the way up to 411 mm.

So-called “Level One” builds feature a choice of Shimano Ultegra Di2 or SRAM Force AXS electronic groupsets, along with 40 mm-deep aero carbon fiber wheels, the aforementioned carbon fiber cockpit, and a carbon fiber seatpost from Ritte’s new house brand, Othr. Retail price is US$7,900 / £7,900 / €7,900.

“Level Two” builds bump things up a notch, moving to a choice of Shimano Dura-Ace Di2 or SRAM Red AXS electronic groupsets, together with a choice of Enve SES 3.4 or 4.5 aero carbon fiber wheelsets, an Enve carbon fiber seatpost, and the same Othr one-piece carbon fiber cockpit. Retail price is US$11,900 / £11,900 / €11,900.

For DIYers, the frameset is offered with or without the Othr cockpit for US$3,950 / £3,950 / €3,950 or US$4,300 / £4,300 / €4,300, respectively, and it’s worth noting that the Esprit will also work with “any traditional round bar and stem setup” when you use the other headset cover that Ritte includes.

UK and EU prices listed above include VAT, and Australian pricing is to be confirmed.

“If you live outside of a region where we have a dealer, we can most certainly ship direct as well,” Grundel explained. “In that case, the customer would pay in USD and we offer a number of payment options to minimize currency exchange costs.”

Whichever way you go, kudos to Ritte for not only offering the Othr cockpit in twelve different length-and-width combinations, but also the ability to choose which one you want during the ordering process. Buyers also get to pick between a straight or setback seatpost. And although there aren’t pulldown menus on the ordering page for other things like crankarm length or gearing, Ritte says all of that can be customized, too.

“We originally had a ton of dropdowns and found that many folks found themselves confused and reaching out to clarify different options, anyway, and the huge number of dropdowns became more of an impediment than a feature,” explained Ritte brand director Elijah Grundel. “We’re always happy to have that conversation and configure things to individual needs. We reach out post-sale just to go over everything the way your dealer or a custom builder would do. So a general post-purchase message would be us asking if the rider has any questions about fit (or if they’d like us to run a fit comparison with their current setup), tailoring their gearing or crank length options, making sure they’ve got the cassette they want, tire widths, etc. The bikes aren’t sitting in boxes waiting for a label; we build them based on the order.”

Bravo.

Ritte provided for me a modified Level Two Esprit loaner, outfitted with a SRAM Red AXS groupset and Othr one-piece carbon fiber cockpit, but also an Othr 40 mm-deep wheelset and FSA SL-K carbon fiber seatpost instead of the Enve stuff buyers would normally receive. There was also the Selle Italia Novus Boost Eco Superflow saddle from the Level One build instead of the Selle Italia SLR Boost Superflow.

No matter, though: none of those substitutions dramatically affected the overall performance of the bike, and the whole thing was still very light at just 7.28 kg (16.05 lb) in my small size, without pedals or accessories.

Breaking free on the Esprit

I’ll be honest: there’s a heck of a lot to like about this thing.

As you might guess given the frame’s proportions, the Esprit is plenty efficient in terms of how well it turns pedaling efforts into speed. It squirts forward with little delay when you apply the power, and there’s a general eagerness to how it responds to either pedaling or steering inputs. Climbing on the Esprit is quite enjoyable as a result – particularly when out of the saddle – as is sprinting. It’s not insanely stiff, mind you, and I’d argue something like a Giant Propel Advanced SL still has a leg up here. But that said, the Esprit is pretty impressive in that respect.

More surprising, however, is the overall comfort level. Even as compared to other bikes I’ve ridden with similar tire-and-wheel setups, the Esprit positively glides over ugly tarmac, smoothing over small imperfections as if it was one of those asphalt trucks laying down a fresh layer of tar. It effectively damps smaller vibrations, but still has enough flex in reserve to take the sting out of bigger impacts, too. Some credit surely goes to the traditional 27.2 mm-diameter round seatpost, but even that can’t account for everything.

Even better is the overall feel, something that’s generally much harder to quantify and far more difficult for brands to provide, but Ritte has managed to hit the bull’s eye with this one. While the Esprit may not be among the absolute stiffest road bikes out there, there’s just enough flex and springiness to provide the sort of lively ride often touted in metal bikes (titanium, in particular). It’s not some ultra-rigid tool; there’s life to it that’s often lacking in high-performance composite bikes, and it’s just a lovely bike to ride all day.

Fit also seemed just about spot-on for me, with a nice, long reach dimension and fairly low stack that allow for either a very aggressive rider position or a slightly more heads-up posture. The split headset spacers make height adjustments pretty easy, too, and it’s nice to see an integrated setup that so readily accommodates headset spacers on top of the stem while you dial things in.

The bike’s handling characteristics may be a bit more polarizing, although even that shouldn’t ruffle too many feathers (and there’s an easy fix, too).

Ritte’s other tagline for the Esprit is that it’s a “race bike for everyday”. Part of that is apparently very fast steering. Although trail is conspicuously missing from Ritte’s geometry charts, the company confirmed my suspicions, saying the trail dimension on my small-sized sample is just 56 mm – quicker than a Specialized Tarmac, Trek Madone, Cannondale SuperSix Evo, or Giant Propel. It’s not a huge difference on paper, but I still found it a little too twitchy for my liking, particularly when attacking steep downhill switchbacks, where the bike had a tendency to dive a little harder for the apex than I really wanted, and lacked some of the stability I prefer when moving that quickly.

But remember what I mentioned earlier about that adjustable fork rake? Ritte prefers not to make a big deal of this, but customers do have the option of fitting different axle inserts to fine-tune the handling. In stock form, my small-sized bike comes with 50 mm of rake. However, installing the 45 mm inserts brings the trail dimension up to a still-quick 61 mm, which I found to provide much more intuitive handling overall and tamed much of the initial nervousness without delving into endurance bike territory.

Riders who want ultra-quick handling obviously won’t have any issues with the stock handling. However, I’d argue that riders who want a “race bike for everybody” might not universally want true race-bike handling, particularly if they plan on doing some light off-roading by taking advantage of the bike’s generous tire clearance.

“[The Esprit] is our full-on road race geo and we don’t intend for it to be relaxed, though the frame itself is comfortable,” Grundel said. “This bike, we feel, sits in a place that a lot of brands have skipped over. Most people just aren’t racing all the time but still want a bike that’s nimble. The fork inserts would be a no cost option, but it’s really not something we want end users burdened with choosing. For most it would just be confusing. Trail is so often misunderstood and we’re working to minimize confusing options. While we’re very happy to customize, we’d prefer to do most of it one on one.”

Nevertheless, the option is there if you know to ask for it.

Some quirks

The devil is in the details, as they say, and I ran into a few that raised my eyebrows a bit.

Perhaps the most questionable is how Ritte uses a number of tighter-radius edges in the design of the Esprit. That normally wouldn’t be a huge cause for concern, except that I noticed how many of those corners appeared distinctly lighter in bright sunlight. Naturally when dealing with any sort of potential problem with carbon fiber, I consulted Raoul Luescher of Luescher Teknik in Melbourne, Australia.

“That looks like fiber bridging: when the fiber doesn’t get into a corner, but rather bridges the gap,” he explained. “This creates a void, which depending on the resin flow, can be filled with resin or not resulting in an air void. With such a small radius corner, I would expect that. The minimum radius should really be 1/4″. I often see problems with these designs.”

So is this an actual problem? Ritte doesn’t seem to think so.

“The frame you (and all current reviewers) received was part of a final testing batch manufactured before full production,” Grundel told me. “In general, a production frame would only stand to get better in terms of fit, finish, and consistency over the run. With unidirectional sheeting there is always potential for loose individual strands and we’ve chosen to avoid any additional beauty layers or cosmetic cover-up on the raw carbon frames. It’s something Ritte has always done on one paint scheme of each model over the years to some extent.

“We’ve generally erred on the very conservative side with anything safety related, be it our production steel bikes or the new Esprit. Our internal testing requirements have all been well above and beyond any sort of commercial requirement in terms of load, cycle count, impact weights, etc. We send everything out for third party confirmation of our internal factory testing. So, suffice to say, I’m very confident these frames are among the sturdiest out there.”

Even if there’s nothing really to see here, I have some other (more minor) concerns.

The hardware securing the fork tip inserts and the cosmetic front brake bolt cover is awfully small, requiring a teeny, tiny 2 mm Allen wrench that I simply despise. It wasn’t an issue when I was playing around with stuff during testing, but then again, the bike was also still pretty new and hadn’t seem much weather. Even high-quality 2 mm hex heads are prone to rounding under the best of conditions, so I’d love to see Ritte move to something a little bigger and more robust here.

Speaking of hex heads, the ones on the front and rear thru-axles of my test bike were worryingly shallow. Ritte used a two-piece setup with aluminum shafts and stainless steel heads. The stainless heads provided some welcome shininess to break up the acres of matte black, but the 5 mm hex fittings just didn’t provide much tool purchase. The other end of the thru-axles thankfully had supplemental 6 mm broaches in case the 5 mm end stripped. Regardless, Ritte has apparently made a running change with all-aluminum thru-axles and deeper 6 mm heads. If you somehow ended up with an earlier Esprit with the same thru-axles I had, I’d ask for replacements to prevent some potential headache down the road.

I also wished the fork tips had defined cradles for the hub axle ends. As it is, the hub is located only by the thru-axle; there’s no “pocket” in the fork into which the hub end caps seat. I don’t think it’s a safety concern, but it does make for a (slightly) more frustrating experience when re-installing a front wheel. NBD.

Build kit breakdown

I’ve gone on at length in the past about SRAM’s Red eTap AXS wireless electronic groupset, so I won’t repeat myself here. In short, though, I think it’s generally good stuff. It shifts solidly (if not quite as smooth as Shimano), the lever ergonomics are excellent and widely accommodating of a broad range of hand shapes and sizes, the eTap-style shifter actuation (left button for easier gears, right one for harder ones) is brilliantly intuitive, and the hydraulic disc brakes offer ample power and control, and run reasonably quietly.

Does the wastefulness of the one-piece machined aluminum chainrings drive me nuts? Do I still wish the brake lever throw was shorter? Do I still not understand why SRAM had to resort to a proprietary chain roller diameter? Yes, yes, and yes. But I still think it’s good stuff overall.

I was quite impressed by the 40 mm-deep house-brand Othr Anywhr 40 wheels (what is it with the bike industry and vowels?). Claimed weight is less than 1,350 g – and they feel like it – the generous 24 mm internal width features a mini-hooked tubeless-compatible profile for greater tire compatibility, and the 32 mm external width is a good pairing with tires that feature a 28 mm printed width for good aerodynamic performance. Bonus points for the star ratchet-type rear hub that’s (unofficially) compatible with genuine DT Swiss internals. Comparatively speaking, they’re even reasonably priced at US$1,750 aftermarket. I’d run these myself.

Ritte’s choice of Vittoria Corsa Next clinchers is a good one for a high-performance all-rounder, too. Although not quite as luxurious-feeling as the brand’s cotton-blend stuff, the Corsa Next nylon tires are nevertheless still admirably fast-rolling and grippy, and the set I’ve been running for the last few months has held up pretty well. No complaints there.

I’m generally not a huge fan of one-piece cockpits, but I think Ritte has done a solid job here. The wide range of sizes is a good place to start, although I’d imagine the company has already fielded requests for something narrower than 40 cm. The compact drops felt good in my hands with their very subtle flare, as did the moderately flattened tops, and the 80 mm reach offers a lot of positioning variation that I sometimes find lacking in setups with shorter dimensions. There’s a little extra versatility baked in, too, with options for fully internal, partially internal, and external line routing. And as promised, it’s “stiff, but not too stiff.”

That all said, it’s nice as a stock piece, but I’m not sure I’d pay US$500 for it.

So do I rate the Ritte?

Without question, the Ritte Esprit was a great bike to ride: quick and eager, remarkably comfortable, competitively light, decently versatile, clean and good-looking, and with a bit of small-brand cachet you won’t get from a bigger label. It’s a decent buy compared to something like an S-Works Tarmac or a top-shelf Madone, but a tougher sell against a similarly equipped Giant TCR Advanced, for example, and consumer-direct brands like Canyon or Fezzari absolutely squash the Ritte on the value front.

Is the answer clear-cut? As usual, the answer is no. But I’ve little doubt this bike speaks to someone out there.

More information can be found at www.ritte.cc.